If you had a dime for every time a teacher, parent, or supervisor told you to use your brain, you’d be rich.

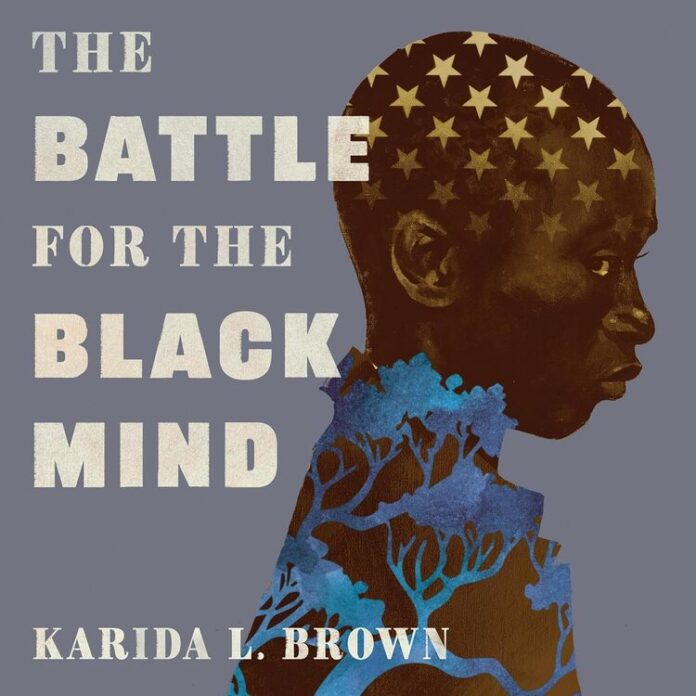

Stop fooling around. Consider what you’re about to do. Act with resolve, not impulse. It’s the best way to work, the optimal method for learning and, as in the new audio book “The Battle for the Black Mind” by Karida L. Brown Ph.D. (Legacy Lit, May 13, 2025), it’s what so many have fought for.

In the months after the Civil War ended, it became apparent to both Black and white people in both the North and the South that education for four million suddenly freed former slaves was “a matter of national security.” It was obvious that those citizens would require formal learning soon, maybe job training. But what kind and how much?

While Mary Smith Peake by then had “laid the foundation” for Hampton University by then, two white men with vastly different intentions traveled south after the war to seize control of Black education. Edmund Asa Ware, who became the first president of Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University) built schools that “aimed at nurturing Black intellectualism and potential,” while General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, who was the first president of Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) had plans to “civilize” formerly enslaved people through physical labor and farm work.

Booker T. Washington was one of Armstrong’s best-known protégés. In 1881, Washington became the first president of Tuskegee Institute and was later instrumental in forming the “Tuskegee Machine” which, says Brown, didn’t altogether help “Black families and shoved a singular curriculum down their throats.” There were forty-five Black colleges and universities in America then, though education for most Black children was still lacking.

It remained so in the Jim Crow era when, although literacy rates grew, education beyond a few years of elementary school was “rare” for Black Americans. By then, says Brown, Black women had stepped up to do the work, becoming teachers, bookkeepers, experts in strategy, fundraisers, staffers, managers, and marketers –sometimes, all at once…

Blending personal observations and experiences with good backgrounding, Brown, a sociologist, oral historian, and professor at Emory University, tells this story in a conversational tone that invites readers to peek down the halls of history’s HBCUs and into classrooms. She writes to readers, rather than at them, which helps to open minds for what’s inside “The Battle for the Black Mind.”

You may not need to be reminded about racism in Black American education, but the secrets Brown shares and the lines she draws are highlighted to seem like new information. Here, readers can see more clearly the connections between the early twentieth-century and now, and how Project 2025 could change the trajectory.

Fortunately, Brown also offers advice and ideas for taking action and ensuring that upcoming generations can win the next “battle.”

“The Battle for the Black Mind” is a lively book that you can read for information, history, or just because. But beware: it might make you want to get up, contact your Representative or Congressperson, and act. It’s the kind of book that’ll make you think.